What is Consent?

The National Domestic Violence Hotline (NDVH) defines consent as a mutual agreement between partners about what they want their sexual experience to be. While some consider consent to simply mean “no means no,” experts say that line of thinking puts all of the pressure on one person to “resist or accept.” Alternatively, the saying “yes means yes” can better be used to understand that consent is an ongoing conversation that ensures all people involved feel safe and comfortable.

What we know about sexual consent can be directly attributed to the types of conversations we have or don’t have growing up. While some parents may think teaching consent at a young age encourages sexual exploration— experts say it actually teaches an important lesson on respect, and even limiting “snacks or TV time” establishes “firm boundaries” that children learn need to be respected.

In this blog, we want to uplift the expertise of several organizations dedicated to providing education, awareness, and support to the abuse of millions of women and men experience each year.

What Does Sexual Consent Look Like?

- It needs to happen every time. Consent should be seen as an ongoing conversation, which means just because we consented to something in the past does not mean that we don’t need to establish that consent again. Additionally, boundaries may change between experiences and in a healthy relationship, boundaries should always be respected. Consenting to one thing also doesn’t mean you consent to other things, and it’s okay to stop at any point if you become uncomfortable.

- Just because you’re in a relationship doesn’t mean that consent isn’t necessary. It doesn’t matter if you’re in a committed relationship, married, the first time, or with someone you know — you’re never obligated to consent to anything involving your own body.

- Implied consent doesn’t exist. Flirting, talking, or even showing interest does not mean consent. Consent needs to be explicit, voluntarily, and enthusiastically provided when agreeing to engage in any physical activity. The absence of “no” is NOT consent.

- If you’re afraid or unable to say no, it’s not consent. Being pressured or forced into sex is behavior among unhealthy and abusive relationships — so if you’re being manipulated or threatened into a sexual activity you are unable to legitimately consent. This includes situations where someone is sleeping, unconscious, or influenced by conscious-altering substances like alcohol, recreational drugs, and some prescription medications.

As mentioned before, consent can be given and taken at any point, and it’s important to remember that even when we consent to sex — that doesn’t mean we consent to pregnancy. Our staff is trained and legally required to assess your situation for coercion and pressure, and we will not provide you with an abortion if that is not what you want. Additionally, while we’re limited in the type of support we can provide, our counselors can help you come up with a safety plan when experiencing abuse. When necessary, we can escort you in and out of our clinic safely, and if there is anything we can do further to protect your privacy and ensure your safety, let our medical receptionists know when you call to schedule an appointment or speak with our staff privately when you arrive.

What Do Healthy and Abusive Relationships Look Like?

According to the NDVH, relationships exist on a spectrum from healthy to abusive, with unhealthy being somewhere in the middle. You can learn more about interpersonal behaviors to understand more about the type of relationship you may be experiencing by clicking here and read below to learn what behaviors the NDVH lists for each type of relationship.

Examples of behaviors in a healthy relationship:

- Communicating (talking openly and respecting each other’s opinions)

- Being respectful, valuing each other

- Trust

- Honesty (but can still maintain privacy)

- Consensual sexual choices (open communication about sexual and reproductive decisions, all partners willingly consent)

- Equity in a relationship, finances (decisions are made together)

- Supportive parenting (both partners are able to parent comfortably)

- Enjoying personal time

Examples of behaviors in an unhealthy relationship:

- Not communicating when conflict arises

- Disrespect

- Not trusting (such as not believing what a partner says, invading privacy)

- Dishonesty

- Trying to take control (a partner feels pressured their partners’ desires and choices are more important)

- Only spending time with your partner

- Not respecting boundaries

- Not mutually discussing finances; one partner assumed to be in charge of

- Pressuring pregnancy, sex, or sexual activity

Example of behaviors in an abusive relationship:

- Communicates in a hurtful, demeaning, or insulting way

- Mistreatment (not respecting thoughts, feelings, or decisions of partner)

- Accusations of cheating or other untrue things

- Gaslighting/denying abusive behaviors as abuse/making the partner believe they are wrong or the abuser instead

- Controlling a partner

- Forcing a partner into pregnancy, sex, or sexual activity. Stealthing is a form of sexual abuse that involves removing or damaging the condom before sex, and some partners may sabotage their partners other birth control use

- Controlling finances (such as not allowing a partner to work or access money)

- Manipulative parenting (attempting to gain power using the children, tells children lies and negative things about the other).

How to Teach Your Kids About Sexual Consent

No parent wants their child to grow up a victim of violence, and with the public education system severely lacking in sex education, parents have due diligence to ensure their children know they are in control of their own body, and that they know to respect others’ bodies, too. You can click here for a list of children’s books centered towards sexual health, respect, boundaries, consent, and more — and read below for some tangible ways to implement lessons in consent in our everyday life:

- Set boundaries and stick to them! Teaching children about consent is teaching them about boundaries. Set firm boundaries in the home and follow through with consequences when those boundaries are crossed.

- Establish physical boundaries. This physical can begin as soon as children are becoming curious about bodies — as early as 4 years old.

- Teaching physical boundaries can be as simple as reminding children that others cannot touch them without being given permission by saying yes, or through consent.

- Parents can also respect their children’s boundaries by not tickling, hugging, kissing, or wrestling children when they say no.

The State of Sex Education In Texas

Public schools in Texas, which serve over 5 million children, are not required to teach sex education. In fact, state law requires that schools providing sex-ed emphasize abstinence as the best method for young people— focusing on that more than any other aspect of healthy relationships and sexual health — and parents are able to request their children not to participate. Abstinence-only sex education is opposed by not only the American Academy of Pediatrics but the American Medical Association and the American Public Health Association.

Over the summer, the Texas State Board of Education held various hearings to revisit and expand the curriculum requirements for sex education for the first time since 1997. Advocates who testified in favor highlighted the need for not only a more broad curriculum, but an inclusive one; including information on gender identity and sexual orientation, healthy relationships and consent, STI awareness, birth control, and abortion. They shared their own experiences as a result of not having access to appropriate sex education, such as not knowing their rights to birth control or abortion, how to use condoms, experiencing sexual assault and rape, and not knowing what healthy relationships or consent entails.

Sexual Violence is a Public Health Issue

The CDC considers violence — including child abuse and neglect, elder abuse, firearm violence, intimate partner violence, sexual violence, youth violence, and suicide — a public health issue spurring the development of the National Center for Injury Prevention and Control in 1992 as a lead organization in the U.S. for violence prevention. Intimate partner violence (IPV) is common and can occur between current and previous partners, between partners of any gender identity or sexual orientation, and it doesn’t have to involve sexual intimacy.

Behaviors of IPV include:

- Sexual Violence – forcing or attempting to force a partner to take part in a sex act, sexual touching, or a non-physical sexual event (e.g., sexting) when the partner does not or cannot consent.

- Physical Violence – when a person hurts or tries to hurt a partner by hitting, kicking, or using another type of physical force.

- Stalking – a pattern of repeated, unwanted attention and contact by a partner that causes fear or concern for one’s own safety or the safety of someone close to the victim.

- Psychological Aggression – the use of verbal and non-verbal communication with the intent to harm another person mentally or emotionally and/or to exert control over another person.

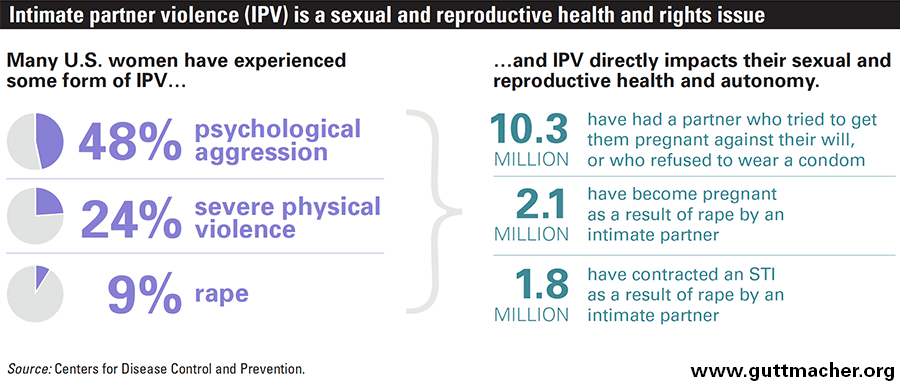

(source: Guttmacher Institute)

Those at risk of experiencing IPV include young people, people with disabilities or mental illness, substance use, people with low self-esteem, witnessing IPV in other relationships, or unplanned pregnancy. The National Domestic Violence Hotline (NDVH), which receives about 20,000 calls nationwide on a typical day, states that IPV accounts for 15% of all violent crime and that 1 in 3 women and 1 in 10 men will experience a form of intimate partner violence, such as physical violence and/or rape; young women aged 18-24 and 25-34 generally experience the highest rate of IPV.

Additionally, most women experienced their first experience with IPV and/or rape before the age of 25, and over 40% of women who were raped experienced their first rape before the age of 18. Nearly 1 in 3 women in college experienced dating abuse; more than half of college students don’t know how to help someone experiencing dating abuse, and 38% don’t know how to get help for themselves. IPV can occur in the workplace, among young teens, digitally through social media and phone, and even during childhood through unhealthy relationships between adults in their lives.

(source: CDC)

Support Is There For You When You Need It

Are you experiencing an unhealthy or abusive relationship, aren’t sure if behaviors in your relationship are something everyone experiences, or had an experience you think occurred without your consent? The NDVH offers free 24/7 support over their phone chat services from trained advocates who can help you explore your specific situation with compassion and understanding.

The NDVH can be reached by phone 1-800-799-SAFE or through their online chat by clicking here. En Español: 1-800-787-3224

Are you a young person experiencing a challenging situation, like a rough break-up or conflict at home? You can also reach out to Your Life, Your Voice over phone or text at 1-800-448-3000. Their secure email form can be found here.

You can also contact the NDVH’s National Teen Dating Hotline, LoveIsRespect, by texting LOVEIS to 1-866-331-9474, chatting online, or by phone.

If you’re pregnant and need an abortion, but can’t tell your parents because it isn’t safe or they wouldn’t agree, you can also reach out to Jane’s Due Process for help getting a judicial bypass, or permission from a court to have an abortion. Call or text 1-866-999-5263 to learn more! The process and abortion are both free.

You can also make an appointment with us via our secure online form or call our office at 512-443-2888